Products You May Like

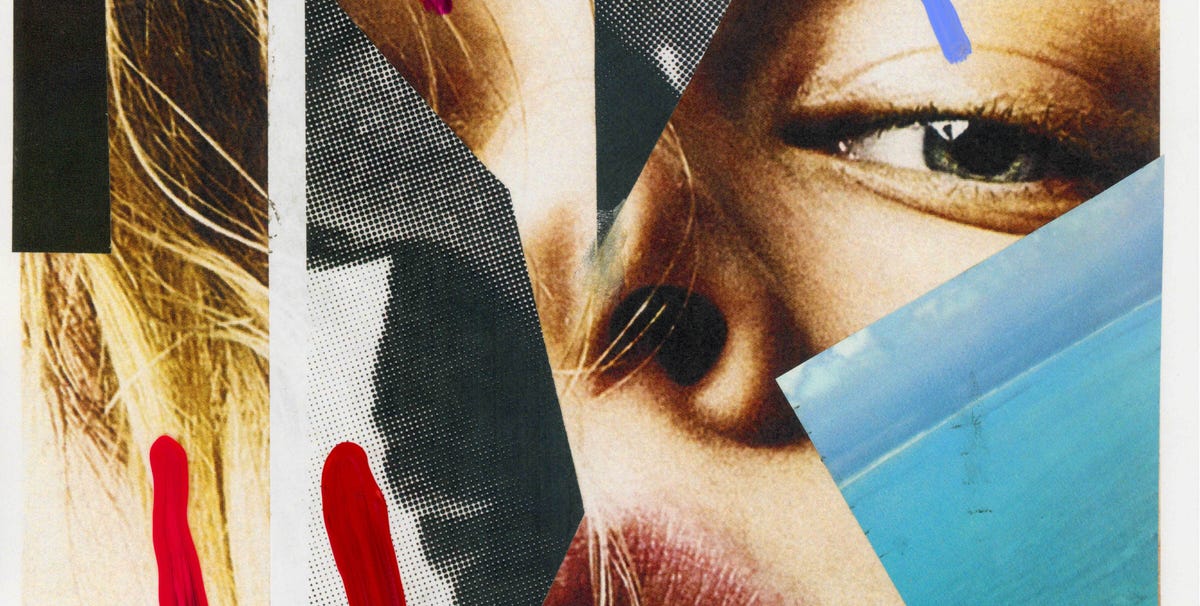

The great poet Sylvia Plath once wrote, “My face I know not. One day ugly as a frog the mirror blurts it back.” I feel you, girl. While many people channeled their anxiety into canning and puzzles during the pandemic, I took it out on my face. Some call it facial dysmorphia, but I call it FaceHate. Instead of dealing with the extreme isolation I felt as a single woman who moved across the country to a new city a few months before COVID shutdowns, I obsessively picked apart my reflection. In Zoom after Zoom, I found myself confronting a litany of internal critiques: The right side of my mouth is slightly downturned. The family jowls have finally caught up with me. When did my right eyelid get so droopy? Faced with such thoughts, I would often decide I was too grotesque to be seen and keep my video off. My Self View, however, was always on.

As the pandemic stretched on, my FaceHate worsened. I developed a habit of immediately grabbing my phone after waking up and snapping a selfie to see whether I looked as repulsive as I had the day before. Were my eyes red? Lopsided? Was my face swollen? Did my skin look…older? I would identify a choice defect of the day and walk back and forth to the bathroom mirror every 5 or 10 minutes checking, checking, checking on it. I was relentless, but I couldn’t make myself stop. I knew I needed help.

So I did something perfectly suited to my new city, Los Angeles. I hired a gorgeous and deeply spiritual model–turned–female embodiment life coach from Topanga, California, named Rachel Pringle to help me establish some healthy self-love practices. I wanted to learn how to spend less time looking in the mirror thinking about what I saw there, but that’s exactly where our work began. Pen and paper in hand, Rachel had me look at myself and list everything that I deemed unworthy. Well practiced at this point, I held nothing back.

According to psychiatrist and neuroscientist Dave Rabin, MD, PhD, “Facial dysmorphia involves an obsession with ‘defects’ in one’s appearance that results in dysfunction in work, social, or home life that is disproportionate to the perceived ‘defect.’” Yep, he nailed it. And as I learned, the more you hate on yourself, the more you hate yourself. “Neurons that fire together, wire together,” Rabin explains. “The more we practice thinking about ourselves as defective, the more inadequate we feel—and this connection gets stronger every time we choose to go down that path.”

To counter the negativity, Rachel instructed me to write down affirmations that focused on who I was as a person, not what I saw in the mirror. I threw on my headphones, pressed Play on some soul-stirring piano music, and gazed deeply into my own eyes. Your vulnerability is gorgeous; I honor your sensitivity; I love that you’re doing this work, I told myself.

This exercise felt just as awkward as you’d expect, but it also forced the heart-wrenching realization that I had become my own punching bag. Praising myself for who I was, Rachel said, was about continually affirming the “me” my FaceHate couldn’t see: a woman doing the very best she could, just longing to be seen.

Despite its New Age roots, there’s actual science behind “mirror work.” The practice, introduced in self-help pioneer Louise L. Hay’s 1984 best-selling book You Can Heal Your Life, was designed to cultivate self-compassion. All that’s required is a bit of time, a mirror, and positive affirmations. Although mirror work has been widely recommended by psychology and self-help practitioners as a means to increase self-acceptance, its effectiveness hadn’t been empirically tested until relatively recently.

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Positive Psychology found mirror work to be effective at soothing the parasympathetic nervous system, leading to feelings of safety and calm. The beautiful thing about mirror work, unlike many self-help practices that just scratch the surface, is that it actually reprograms the critical eye by creating new neural pathways, or thought patterns, that become dominant over time and improve your relationship to yourself. The practice isn’t a cure-all for the screens that look back at us daily, but it’s a start.

The next step in my face-love journey was reading motivational speaker and best-selling author Mel Robbins’s latest book, The High 5 Habit, published last September. Robbins has her own version of mirror work in which she encourages people, right after they brush their teeth in the morning, to look at themselves in the mirror, set an intention for the day, and then give their reflection a high five.

She readily admits smacking your bathroom mirror—er, high-fiving your own reflection—sounds crazy, but she swears it instantly silences your internal critic and replaces it with I believe in you, we’ve got this, let’s go, pick yourself up, come on now, keep going. “When you’re giving yourself a high five, even if you think you’re a piece of shit who doesn’t deserve it, you get a hit of dopamine,” Robbins said in an interview with the Financial Post. “It’s neurologically impossible for your brain to beat itself up and accept a high five at once.” Silly as it made me feel at first, I ultimately found high-fiving myself solidified me as my new best hype woman.

Once I started to experience the transformational effects of the practice, I felt like a superhero. I was rewiring my brain and becoming more tuned in to the me that mattered most. Believe it or not, I recently found myself murmuring, You got this, baby girl, as I penciled in my eyebrows. I control the mirror now! And the time I spend looking at myself on Zoom now feels less evaluative, more encouraging. Don’t get me wrong: I still have bad moments when I spin out thinking I need Botox ASAP (my car’s rearview mirror can be a trigger), but I am quick to catch myself. What is it you need to feel? What would your heart say? How can I help you feel seen? And then if even that feels like too much, I just “Hide Self View” and call it a day.

This article appears in the May 2022 issue of ELLE.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io