Products You May Like

Long, khaki schoolteacher skirt, tailored men’s white shirt and black blazer (stiff collars), ’70s dress with brown buttons down the front, oversize cardigan (with pockets), men’s wool scarf, floral grunge dress, lace-up military boots, trench coat, white baby-doll dress, denim cutoffs, tiny shoulder purse, vintage brooch, flannel.

The list, dated Aug. 12, 2003, is jotted down in runny black ink in a notebook with frayed edges. Unlike other indecipherable scribbles—another page reads: “Dinner with M. Cute bartender. Crying.” (Who’s M? And why was the bartender crying? Was I crying?—I know exactly what this one is.

That summer was my first in New York. The first assault of the garbage fumes and gusts of enveloping hot wind off buses and sidewalk grates, the first ride on humid subway cars crowded with the thick laundry smells of drugstore deodorants and provocatively dressed summer-internship girls daring other passengers to look. I’d been in the city about six months, a period that was, for me at 19, marked by severe yet exhilarating loneliness when I’d become acutely aware of my lack of sophistication—startling, really, since I’d spent my teenage years in a New Jersey town a mere 50 miles away—and longed to correct it. Everyone I met quoted books I’d never read, movies I’d never seen, and people (always, always on a first-name basis) I hoped to meet.

On certain days, there seemed to be so much to take in—so many important instructions veiled in the sentence (from the same notebook) “Sarah shops at Barneys. Might as well live with her parents on the Upper East, you know?”—that I began making lists. Long and short lists of authors to read (was it Ca-pote or Ca-poe-tee?), neighborhoods in which I might like to live (Brooklyn?), foods to become fluent in (Thai, Vietnamese, vegan), and, as I was so often instructed, the “right” people to befriend, and the “wrong” ones, too.

That August note is an example of one such list. With fall approaching, that back-to-school time when reinvention seems most possible, I studiously wrote down the items of clothing I’d decided would update my personal style: a list that was culled from the wardrobes of two women in particular—both sometime New Yorkers by way of someplace else—whom I’d never met but who, in their distinct ways, seemed to know something about the city that I didn’t, and it showed, as it often does, in their clothes.

I became aware of the first woman through a lunchtime regular at the restaurant, rated first in the Zagat guide that year, where I waitressed. This customer, let’s call her L., worked as a reporter for NY1, the local cable news network. One day, as I dropped off her roasted monkfish, L., who knew from one of our previous attempts at small talk that I was studying journalism, asked what I wanted to do with my life. Not yet knowing what my answer meant and with graduation far enough away that I felt I had a lifetime to figure it out, I confidently said, “Writer.” L. smiled a smile I would not understand until many years later. “Well,” she finally said, “you must be obsessed with Didion, then. And you’re sort of small like her.”

Who?

Though I did not mean to, I looked down at my feet. “Her books will change your life,” L. quickly assured. “She just has this way of saying things that we’re all thinking.” She suggested I begin with Slouching Towards Bethlehem, a collection of essays. I added it to the list.

L. was right. I won’t talk about the many ways in which that book or Didion’s other work has propelled my life since then—Didion readers will recognize the beginning of this essay as a fan’s imitation of “On Keeping a Notebook”—only about how I came to deconstruct her outfits into pieces I wanted to incorporate into my own.

To talk about why Didion’s look appealed to me is to talk about what it means to be a tiny woman. “My only advantage as a reporter is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate,” Didion writes, “that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.” That’s it! I thought. Ever since I was old enough to shop in the adult section, I’ve been a static size zero. Not the size zero of the tall and slender models and actresses who possess a certain imposing regality, but a size zero that, in combination with my crippling shyness, often makes my presence go unnoticed, except for the times when I am simply remembered (as I was once informed) as the “small, quiet one”; that when I showed up to interview movie directors, authors, and city officials as a reporter for the newspaper where I used to work, they seemed peeved that the paper didn’t deem them important enough to send an adult; that even now, at 27, I’m so often mistaken at professional gatherings for someone’s teenage daughter that I have become comfortable in the role, petulantly crossing my arms in front of my chest when I feel reluctant to engage in conversation.

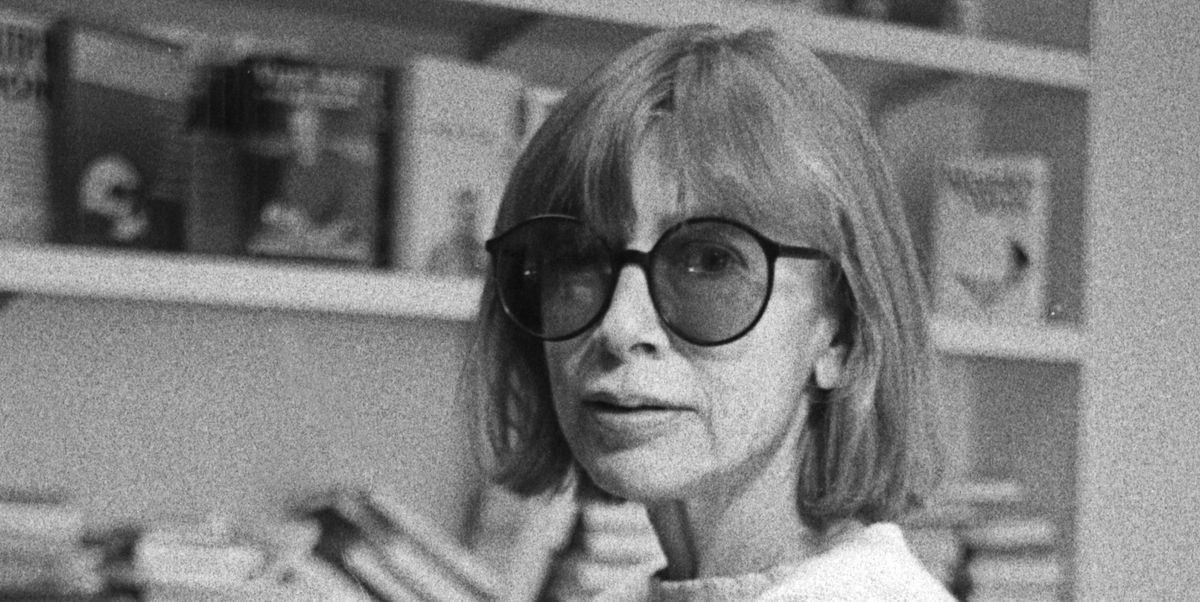

And here was Joan, telling me this is an advantage! And oh how she wore her physical smallness. A Google image search reveals Joan, never one to wear attention-seeking prints or cuts, in tough, oversize blazers, swaddled in masculine wool scarves; in a long, feminine wrapskirt and a nondescript long-sleeve top, her arm elegantly draped over the back of a large, white armchair in her California home; in high-waisted gray trousers and a white T-shirt in the hallway of her New York apartment; in modest turtlenecks and austere oxford shirts, her eyes so often hidden behind those saucer-size shades. Except for a photo in which she wears a movie star-like evening dress and poses in front of a yellow Corvette, she’s often wearing what we think of as plain clothes. (Perhaps so as not to intimidate or distract her subjects from surrendering to her notebook.) And yet there is such a dignity, such an intelligent sophistication about her look that restraint, it occurred to my Jersey self for the first time, is much hipper than a cry for attention.

But the thing that offset Joan’s quiet presence was her robust, at times ruthless, intellect and prose. At 19, I couldn’t claim either. Which is perhaps why I was also drawn to the aggressive, self-assured street style of the second woman, the antithesis of Didion (by which I mean me) both in temperament and physicality. I’d see her strolling around the East Village and recognize her, only vaguely, because I’d watched Larry Clark’s Kids in high school.

That fall, as it so happened, in an NYU class earnestly titled “Magazine Writing,” the professor handed out Xeroxed copies of Jay McInerney’s New Yorker profile of Chloë Sevigny (“Chloë’s Scene”), written almost a decade prior to my arrival in New York. “Some people say Chloë is what’s happening in the street,” McInerney writes. And she was certainly still happening in 2003 on my street: She peacocked around the East Village in Popsicle red lipstick, frayed denim cutoffs topped with retro white blazers, and daringly short vintage dresses paired with menacing military lace-up boots—an undeniably cool look, I thought, that suggested late nights and interesting people in cigarette-smoke-filled apartments. If Joan felt she was “unobtrusive,” then Chloë, judging from the way the energy of a city block would shift when she walked down it, heads turning and the summer internship girls whispering, knew she was not and seemed to like it. She pursed her lips at passersby in what seemed like an intimidation tactic, a cobra fanning its hood. And she was entirely unembarrassed in her pursuit of all things cool. She actually was cool in a way I never would be. Chloë need never make lists.

It may seem a sartorial and moral sacrilege to group these two women together. Joan, the distant granddaughter of California settlers, grew up in the “dark houses” of Sacramento, as she writes in Where I Was From, and as a child was dressed in “an eccentric amount of black.” Chloë is from the upper-class town of Darien, Connecticut, or “Aryan Darien” as she would later derisively call it in the press. Where Joan wrote about the moral disillusionment of the Haight-Ashbury youths in the ’60s, “where the missing children were gathering and calling themselves ‘hippies,’” it could be argued that Chloë, had she been alive then, would have been a banner-carrying member. Where Joan has confessed to her debilitating anxiety and sleepless nights, Chloë, the nighttime It Girl of the ’90s that she was, has always seemed sleepless by choice, harboring no apparent anxiety about it. But where these women overlapped their inability or unwillingness to placate, to commiserate, to grease the wheels of social interaction with small talk and polite smiles—I saw myself.

That Joan and Chloë, 40 years apart in age, should become style icons for the same person had of course less to do with them as individuals and more to do with the way that I was then (and in some ways still am): that often I wanted to be invisible, except when I didn’t and felt depressed when I was; that New York has sometimes felt like an “extended leave” from reality, as Joan writes in “Goodbye to All That,” except for the times when I have felt lucky to be taken into the circus permanently; that I never could decide whether New York was about reckless, joyous social consumption or if it was a place I could go out less and write more. ( Joan eventually decided it was not.)

To this day, when I shop, it’s as if I’m wearing one of those WWJD bracelets, except the J is for Joan, and sometimes it’s also a C. I stand in a store and hold up a vintage blouse, wondering whether Joan and Chloë would wear it, because, you see, it has to be approved by both, or rather by my own imagination of their competing tastes. Years later, the two are still an organizing principle—the hybrid style so long honed that the idea of deviating is frightening. My closet is an eclectic combination of Didion’s conservative sweaters, demure cardigans, and ankle-length skirts hanging next to Sevigny’s denim vests, playful minidresses, and tough treaded and heeled boots. Though lately, perhaps because I’m no longer 19, Joan has been winning; last month, a vintage biker jacket was relegated to the back shelf.

But blind adoration for people you have never met has its dangers. A couple of years ago, I interviewed Chloë at a party. As an interviewee, she was fine—no more nor less capable of stringing together press-friendly sentences than other actresses—but when I approached her, she let out a tired sigh and barely made eye contact. The whole thing lasted no more than five minutes. Still, I loved her nautical blazer with brass buttons over a fitted black minidress, paired with towering black ankle boots and cotton-candy-pink lipstick. In fact, I soon had a blazer just like it.

That same year, Joan’s brother-in-law, journalist and author Dominick Dunne, died from cancer, and I was assigned to put in calls to people who knew him to gather material for a tribute. “Call Didion,” a colleague told me. “I think she’s in New York right now.” A few short, pleading calls later, I had Joan’s home phone number. I sat at my desk staring at the digits jotted down in my notebook, paralyzed by the prospect of dialing. Then I did.

“Hello?” a woman’s voice answered. I didn’t speak.

“Hello?” the voice said louder.

“Yes, hello. I’m looking for Ms. Didion?” I finally said.

“Who’s speaking?”

I introduced myself. “I’d like to speak to her for a story I’m writing.” (Best to be vague, I thought.)

There was a pause.

“She just stepped out,” the voice said.

I left my name and number. My first thought when I got off the phone was that, despite my assignment, I hoped she wouldn’t call me back and that I wouldn’t have to talk to her. My second was that I just had.

This article originally appeared in the January 2011 issue of ELLE.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io