Products You May Like

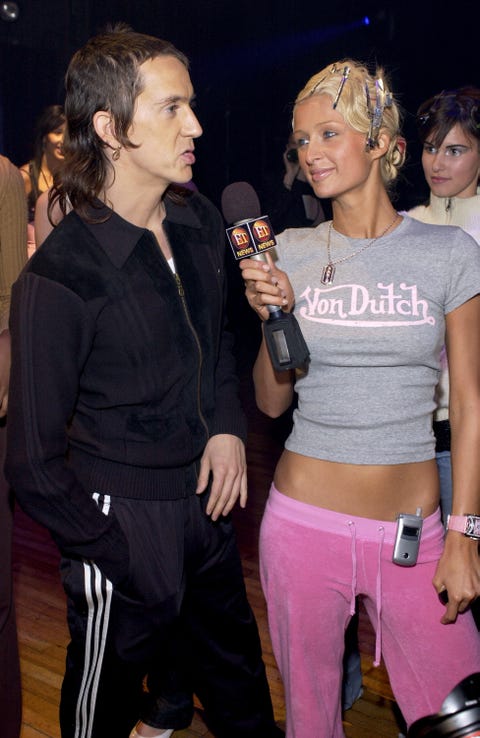

Getty Images; Courtesy of Hulu

Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

Paris Hilton, one of the most prominent Von Dutch wearers in the label’s heyday, is asked at one point in the Hulu miniseries The Curse of Von Dutch if she would ever re-wear their pieces. “Probably as a joke,” she replies.

When you think of the label, your mind probably travels back to the early aughts, the era from which high fashion is currently engaged in mining every going-out top, Juicy sweatsuit, and UGG boot. But Von Dutch, known for its trucker hats worn by everyone from Britney Spears to Anna Nicole Smith to Gwen Stefani, actually dates back much further: to midcentury hot rod artist Kenneth Howard, who made a name for himself with his surreal and gruesome artwork. (“Von Dutch” was his one of his nicknames.)

In Andrew Renzi’s documentary, that fashion origin story gets interwoven with true crime: House of Gucci for the Kitson set. The talking heads behind the label, many of whom seem imbued with a SoCal-specific form of brain poisoning, lay out a tale of intra-brand rivalry, complete with gun-waving. murder, suitcases full of cash, and plenty of wrangling over who really “owns” Von Dutch. But it’s also a parable about the ever-roving re-appropriation of a fashion brand and how quickly style can travel from outsider statement to mainstream to a “joke,” and maybe back to the mainstream. (In recent years, Addison Rae, Megan Thee Stallion and Emma Chamberlain have been spotted wearing Von Dutch, in a move that may or may not be accessorized with irony.) The series also fits into the burgeoning trend of fashion-tainment: when a luxury name like Balmain is wading into territory like a scripted TV series, more mass entrants are likely going to follow. And Von Dutch has no shortage of stories to tell.

Even its origins are disputed; the Americana-heavy, car-culture-inspired brand has three different people claiming they “created” it based on Howard’s iconography: Ed Boswell, Mike Cassel, and Bobby Vaughn. By the 2000’s, Vaughan had sold Pamela Anderson on Von Dutch while on the set of her show V.I.P., a coup that led to dressing Tommy Lee for his Cribs episode. With the help of marketer Tracey Mills, who counted Kanye West and Halle Berry as friends, the styles caught on among the kinds of A-listers who appeared in the pages of US Weekly. They were proletarian cosplay for celebrities at leisure, studiedly casual and perfect for paparazzi-dodging (or courting.) Gifting became one of the hallmarks of the brand; big names could come to the store and walk out with whatever they wanted. And its customer base transcended genre: stars of pop, rock, and hip-hop all sported its logos, as did the new breed of celebutantes. Many of them mentioned being drawn to the brand’s authenticity and rocker edge. Hilton tells the filmmaker that Von Dutch “was free, it was playful, it was cute, it was iconic.” She and Nicole Richie stopped at the store and emerged with “50 shopping bags” before going to Arkansas to film The Simple Life; the pieces ended up comprising much of their wardrobe on the show.

Midway through the series, self-proclaimed “king of fashion” Christian Audigier enters the picture and sends the celebrity-chasing into overdrive. That tabloid exposure got the word out to a public who snapped up its ribbed tank tops and ultra low-rise jeans (“I like these because they don’t really have, like, a waistband,” says one shopper, shown in a news clip.) But Audigier overshot the mark, putting the logo on energy drinks and dog clothes. Von Dutch became the second-most-counterfeited brand in the world, but also one of the most diluted.

The arguments over authenticity and ownership only heated up from there. As it became ubiquitous, some of the original hot-rod fans took to calling it “Von Douche.” Cassel considered it “celebrity, name-dropping, cheap style” that “doesn’t last, doesn’t stick.” As with many surf, skate, and motorcycle brands, the spirit of the original subculture felt like it was being leached out. And while the documentary doesn’t delve that deeply into race, it’s hard for a viewer not to notice that many of those originally associated with the brand and responsible for its early success were people of color, while those who took over, reaping the rewards and dollars, were white.

When Howard, the artist behind the original Von Dutch, was posthumously exposed as a bigot in 2004, a backlash against the brand began brewing. But by that point, the Y2K fashion bubble had burst, and its stock was already headed on its way down. Now, it seems to be embarking on its fourth life, aimed at an audience that may or may not know its complex history—proof that in fashion, the story is never really over.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io