Products You May Like

From Gypsy Sport’s rule-breaking, anarchic looks and Bárbara Sánchez-Kane’s refreshing upending of gender norms to Barragán’s embrace of body-conscious silhouettes and LRS’s take on American streetwear and sportswear, this quartet of brands fronted by young Latinx designers is creating a new vision of what fashion can be—as seen through their own highly individual lenses. As part of our partnership with the CFDA, ELLE spoke to all four—Rio Uribe, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane, Victor Barragán, and Raul Solís—about their design influences, the connection between fashion and politics, and how their heritage is expressed in their work.

Gypsy Sport

Gypsy Sport is meant to be worn by everyone, no matter your race, gender, or sexual orientation. In fact, inclusivity is so embedded in the brand’s DNA that it’s part of founder Rio Uribe’s origin story. Since childhood, the 33-year-old designer has been making clothes for his six younger siblings—four brothers and two sisters, to be precise—zhuzhing up hand-me-downs with a creative flair and transforming them into dapper chic non-binary looks that would earn Harry Styles’s approval. “I remember cutting lace from my mom’s lingerie and sewing it onto the collar of a T-shirt,” he recalls with a laugh. In 2005, Uribe left his home in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley and moved to New York City, where he took on odd jobs like delivering dumplings and organizing Paul Frank inventory before landing a gig in the stock room at Balenciaga. Once he worked his way up to director of merchandising, Uribe’s role began to include travel, and lots of it. Then, in 2012, like so many millennials during the aughts, he launched a Tumblr and called it “Gypsy Sport” after the breed of horses he considers “elegant and androgynous.” Later that year, Uribe’s brand was born, and he was named one of the winners of the CFDA’s Fashion Fund in 2015.

“Why should we categorize people by their taste in clothing?” Uribe asks before stressing that he hopes gender-neutral wares are not just a trend, but a lasting movement. High-profile fans like Lourdes Leon and Jaden Smith subscribe to Gypsy Sport’s sartorial ethos of “breaking all the rules.” For Uribe, that means no limitations with fashion choices, especially in regard to his heritage. His spring 2021 show featured Hispanic models of all genders, sizes, and skin tones to highlight diversity within a specific culture. “I wish people understood that Hispanic and Latino people in America are part of a bigger diaspora and a lot of us are still trying to reconnect with our roots and understand who we are,” he says. “We are just as American, if not more native to this nation, than any of the people here. It’s important to remind ourselves and each other that we belong.” Going forward, Uribe hopes to lead by example and inspire the next generation of Latinx designers to take chances and forge their own path. “We’re a huge part of the industry, but more so behind the scenes,” he says. “I’m really excited to see what the future has in store.”—Claire Stern, Deputy Editor

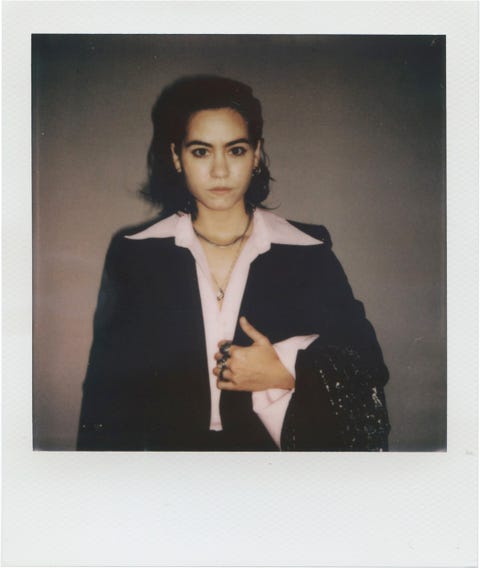

Bárbara Sánchez-Kane

“Mexico has long been dominated by a very macho culture,” says Bárbara Sánchez-Kane, who grew up on the country’s Yucátan Peninsula but has called Mexico City home for the past two years. It’s the same attitude that led the designer to pursue a degree in engineering before enrolling in Florence’s Polimoda fashion school. “Careers in art or design are not generally accepted, so I was very afraid to pursue something artistic.” Nevertheless, it was her native country, from its colors to symbols such as the calla lily, that provided the creative fuel that Sánchez-Kane needed for her senior thesis and subsequent collections.

When the designer made her New York Fashion Week debut in 2016 with a collection titled “Citizen,” which referenced then-President Trump’s anti-immigration policies, many critics were surprised to learn that the young talent was Mexican. Thus Sánchez-Kane has made it her duty not only to promote mexicanidad abroad, but to examine her culture in both its glory and its faults and challenge gender norms while placing an emphasis on community (all Sánchez-Kane garments are made in Mexico, down to the fabrics).—Naomi Rougeau, Senior Fashion Editor

Barragán

The models walking in Victor Barragán’s spring 2021 show wore mismatched contact lenses, one with an overlay of the Mexican flag and the other showing the American flag. It’s the perfect way to sum up the designer’s own lens on his two cultures. Barragán divides his time between his hometown of Mexico City and his adopted hometown of New York City, and his brand, Barragán, often touches on the iconography of both places—for that same spring 2021 show, he referenced the pyramids of Teotihuacan and street clown costumes in Mexico. The Zona Rosa in Mexico City, known for its vibrant LGBT community, also inspired much of his body-con, cutout-heavy aesthetic. “I really was inspired by this idea of, ‘Oh, I feel amazing. I want to wear this, I don’t care what people think,’” he says. That sense of body positivity also extends to his size-diverse casting, still an all-too-rare occurrence on the runway.

Growing up in Mexico City, he says, “I didn’t feel like I could connect with a lot of the designers that I saw, because everything was too far from where I am from.” After studying architecture and industrial design, he moved to New York, where he found a community of fellow Latinx designers, artists, and other creatives. “We felt left out for so long,” he says. “Now it’s really empowering to work with each other and show similar faces and shades and colors, like you see in your family and back home.” He became a CFDA Fashion Fund finalist in 2019, and as his platform has grown, he’s used his brand’s Instagram, which boasts over 100,000 followers, to post about issues important to his community, like the movement to abolish ICE. He’s judicious about what he uses his platform for: “I don’t want the brand to become this performative political message all the time.”—Véronique Hyland, Fashion Features Director

LRS

Raul Solís is not in the business of being dishonest. The Mexican-American designer, who hails from Los Angeles and currently works and resides in New York, worked under Lazaro Hernandez and Jack McCullough at Proenza Schouler for roughly five years before starting his own label, LRS. Solís’s work is post-minimal, post-modern, and deconstructionist in nature, but overall he describes his clothes as “American streetwear and sportswear.” He is in touch with his Mexican culture, as seen in LRS’ early seasons via hand-crocheted knits and thigh-high neon cowboy boots, both produced in collaboration with local Mexican artisans. While Solís is incredibly proud of his heritage and loves to use his platform to speak up against injustice, he first and foremost designs from a place of total honesty. “I’m always very, very proud of my culture,” he says. “But I also don’t want to be forcing my culture… for the sake of just doing it. I’d rather speak on things that feel really honest to me at that very moment.” A recent example that speaks to the authenticity of Solís’s voice is a red-and-white striped gown from spring 2021 which features phrases like “Stronger Together” and “No Justice No Peace.” Designed at the height of the pandemic and the racial justice movement in summer 2020, the dress functions as a beautiful design piece while showcasing an important message that he felt was necessary to broadcast at such a pivotal moment in American history.

As far as Latinx-American inspiration goes, Solís mentions a designer who creates from the heart without feeding too much into Latinx stereotypes of design and dress, something Solís prides himself on in his own work. “I always looked at Narciso Rodriguez for Calvin Klein as a huge reference of being Latin,” he says. “[He] really moved forward in his own voice, aside from what design stereotypes people think of versus what Latin designers actually design.” Solís recognizes the impact of Latinx designers in America who came before him and did “great work by showing codes of Latin style,” but he hopes that, going forward, Latinx-American design will not be so tethered to archetypes. “I feel like we’ve outgrown those codes,” he says. “We don’t need to touch on them to show our admiration for [our] culture. We can move forward and have different ways to communicate what it is to be Latin proud.”—Kevin LeBlanc, Fashion Associate

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io