Products You May Like

Dua: Instagram; Juicy: Getty Images; Courtesy of the brands.

Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

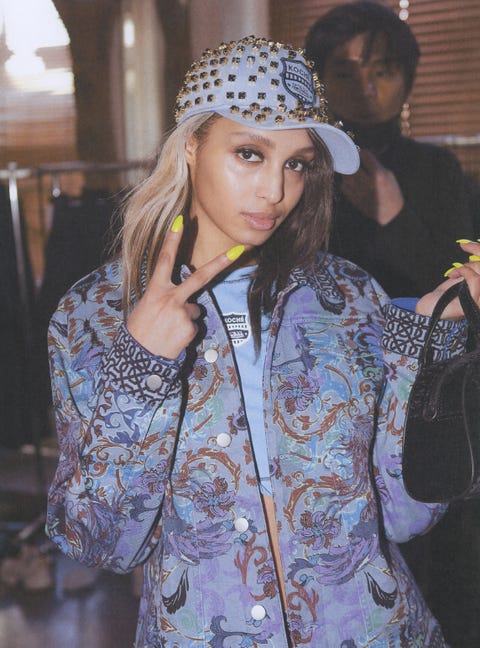

It might have been the return of low-rise jeans that broke people. Every other aughts craze, from UGGs to Juicy Couture sweatsuits, had had its high-fashion moment by that point— the former collaborating with “It” names like Telfar and Molly Goddard, and the latter getting a renaissance on the Vetements couture runway and a collab with Parade. TikTokers are even digging into the rich oeuvre of Ed Hardy. And this season, the bleeding-edge-cool Parisian brand Koché linked up with Von Dutch on trucker hats, bowling bags, and T-shirts. (Designer Christelle Kocher said she was inspired by the style of Britney, Justin, and Paris, no last names needed.)

But pelvis-skimming denim was a harder sell. One person on Twitter said she was responding to their revival “like a vampire responds to a tanning bed.” A viral three-part TikTok series, by Carly Aquilino, shows an anguished woman lamenting, with an operatic level of vocal fry, “the comically large belts” and “the layering” that constituted Y2K style, as images of low rider-clad Gwen Stefani and Christina Aguilera flash behind her. The era’s bizarre looks are less an uncanny valley than a chasm we dread falling back into.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

And yet, there’s not much that can be done to fight it. With Gen Z embracing trucker hats for the first time and Gen X’ers like Kim Kardashian returning to the fold of the velour sweatsuit for her SKIMS line, everything uncool is cool again. It’s hard to imagine a 2000’s trend that hasn’t dazzled us like a crystal-bedecked Razr. (For what it’s worth, those are back, too.) While no one is compelled to wear anything they don’t want to simply because it’s newly deemed on-trend again, thinking we can stem the tide of these revivals shows a misunderstanding of how fashion works. This is what always happens: every era brings once-reviled items we’d forsworn to our metaphorical donation pile back to the surface. Freud would have a field day.

Even ’10’s style seems to be showing an uptick in relevance, challenging the old saw that it takes 20 years for something to be considered “vintage.” There was the revival of the hit Isabel Marant wedge sneaker in June and the interest in O.G. Gossip Girl style stirred up by the show’s reboot. (Balloon-hemline silk dresses and round-toed Mary Jane heels might be the next castoffs to pop up.)

For those who are encountering these trends for the first time as adults, their novelty seems like the primary appeal: when Addison Rae wears a trucker hat, she’s not likely to be aware of the item’s Kitson-era history. But for those looking at it from a more distant vantage, part of the concern might be wrapped up in the less-than-enlightened body standards of the time (low-rise jeans were often accompanied by the expectation of Britney abs) or the inherent classism of some of the trends (like trucker hats, worn by celebrities and fashion people as a kind of working-class cosplay) or even their association with the kind of predatory paparazzi culture that has recently led us to re-evaluate pop figures from Britney Spears to Paris Hilton to Jessica Simpson. Our associations aren’t just with the clothes themselves, but the context that clings to them.

The time many people had to devote to indulging their nostalgia and re-evaluating what they used to love during the pandemic explains the everything-old-is-new-again quality of recent fashion, where, just as it does in Hollywood, a time-tested reboot so often wins out over something brand-new.

But it’s not just nostalgia that’s driving this phenomenon. It’s our unresolved relationship to the whole epoch. When something pops back up on the horizon like this, it’s often a sign that we didn’t deal with it properly on the first go-round, and that’s why these trends aren’t simply random recurrences. It’s no coincidence that they’re floating back up at a time when we are re-evaluating so much about this time period. The Depression-era styles of the ’30’s found a surprising new resonance in the recession-stricken ’70’s, and when old, regressive views of femininity took hold in the Backlash ’80’s, they brought with them a host of ’50’s revivals that recalled another repressed time. Now, as we look back at an era that saw the dawn of reality TV and social media as we know it, we’re questioning how that era shaped and perhaps harmed us. And now that the past is all easily accessible, a Netflix stream or a Google search or an Instagram rabbit hole away, it’s never really past.

To make our peace with, and perhaps even enjoy wearing, these clothes again, we need to grapple with what they once meant, and what they mean to us now. As designer and LVMH Prize finalist Conner Ives told me earlier this year, the Y2K notes he strikes in his work are accompanied by a new, less restrictive approach to fashion, “the shedding of the whole idea of what we can and can’t do.” Perhaps we can all find a way to make like a TikToker and embrace them like it’s the first time.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io