Products You May Like

Ilia J. Smith, a 40-year-old nurse practitioner in Dallas, never suspected she’d be confronted with a life-threatening health concern in her thirties. She was a medical professional. She ate well, worked out regularly. Sure, she spent a lot of time basking in the sun wearing low-SPF tanning oils, but as a Black woman, she wasn’t worried about sun protection. Several years earlier, a friend of hers, who worked as a physician’s assistant in a dermatology practice, flagged a mole on her thigh during a day at the spa, but Smith brushed it off as a birthmark.

Fast-forward to January 2021. Smith, now the mother of a young child, is lying on a plastic surgeon’s table with a gaping hole in her leg. “They had to remove a piece of tissue that was 8.5 centimeters wide and 4 centimeters deep out of my thigh,” Smith says. She was diagnosed with skin cancer—malignant melanoma—last December. “I was floored. I asked my dermatologist how rare this is, especially in African Americans.”

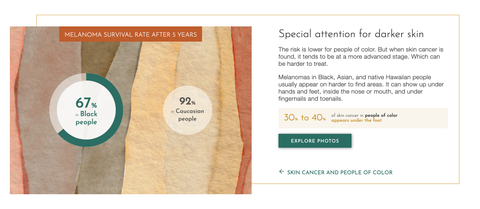

Smith’s surprise isn’t entirely unfounded. The likelihood of women of color getting skin cancer is comparatively low. According to a 2009 report in the Journal of the Dermatology Nurses’ Association, while rates of skin cancer in the United States are about 35 to 45 percent among Caucasians, they are 5 percent or less for Hispanic and Asian patients, and between 1 and 2 percent for Black patients. But two insidious factors can worsen outcomes: First, relaxed attitudes toward tanning among patients of color can amplify risk. “My Latina patients have no problem getting a tan,” says Alicia Barba, MD, a dermatologist in Miami. “Some of my lighter-skinned Black patients [also tell me] they feel prettier with a tan.” Second, the disease is often diagnosed at more advanced stages in patients of color, which means it could be much more deadly by the time it is found.

This is particularly worrisome where skin cancer is concerned, says Jared Jagdeo, MD, an associate professor of dermatology and director of the Center for Photomedicine at SUNY Downstate Medical Center. “Skin cancers usually present very differently in the skin of patients of color,” he says. “Especially basal cell cancer. It’s not only the most common skin cancer, it’s the most [frequently occurring] cancer, and oftentimes presents very differently in darker skin.” Miami-based dermatologist Patricia Rivas, MD, says that for Latina patients, basal cell carcinomas “can start out looking like a pimple that doesn’t want to heal—they have no idea that, unfortunately, that is what cancer can look like in the beginning.”

The information disparity is part of what spurred UK-based medical student Malone Mukwende to team up with two staff members at St George’s, University of London, to create their own handbook filled with images of clinical conditions in skin of color. “We need to start with medical schools and health care institutions,” Mukwende says. “The very first step is [these institutions] taking accountability for the lack of diversity in curriculum, which is part of the reason people are literally dying. [After that], it’s very important to put changes in place, and watch to see if they’re yielding any results.”

Stateside, tech start-ups, and skin care brands are working hard to close the information gap. The digital platform Hued has partnered with Vaseline to connect patients with local health care providers of color, and Vaseline has also sponsored a training module on diverse skin care for clinician site Medscape. A new self-check microsite called Self Exam Beautifully, created by Neutrogena and the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery pinpoints areas where melanoma is more likely to appear in skin of color, like the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

Diversifying the medical profession will also help. “Patients of color are much more likely to wear sunscreen or get screenings if a dermatologist of color is telling them to do so,” says Mona Gohara, MD, an associate clinical professor of dermatology at Yale School of Medicine. And yet “dermatology is one of the least diverse specialties,” she says.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.4 percent of Americans identify as Black or African American, and 18.5 percent as Hispanic or Latino. But just over 3 percent of dermatologists are Black, and less than 5 percent are Hispanic.

Until medical schools and mentorship programs succeed in efforts to yield a more diverse pool of derms to choose from (as recently as 2020, just 65 of the 796 applicants for dermatology residencies were Black or African American, and only 39 were Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish origin), there are a few things people of color can do to improve their own outcomes. First and foremost: Schedule an annual skin check with your dermatologist, and make sure you are scanned for skin cancer, says Karen Kagha, MD, a Harvard-trained cosmetic fellow. Also, “reapplying SPF 30 or higher every two hours is a must for all my patients, no matter their skin color.”

The need for greater diversity in dermatology—and all areas of skin care—is urgent. For her part, Ilia Smith has two practitioners of color—both Black women—to thank for her skin cancer survival story. First, her physician assistant friend, who originally alerted her to the quarter-size mole (several years later, when Smith hit it with her fingernail and a piece of it flaked off and bled, she immediately sought help). Second, her doctor. After looking through the photos of every Dallas–Fort Worth area dermatologist on Zocdoc, Smith found DiAnne Davis, MD, a cosmetic dermatologist at North Dallas Dermatology Associates. Davis promptly biopsied Smith’s malignant melanoma. “I just wanted someone who looks like me,” Smith explains. “Someone I can feel comfortable disclosing my tanning habits to, and someone who would understand where I’m coming from without any judgment.”

Smith’s life may have been saved, but others haven’t been as fortunate. “[Skin conditions] such as melanoma are being diagnosed too late,” Mukwende says. “It boils down to the way we are as humans. When we don’t understand something, we often revert back to the original way we learned about it. If the first way we learned about skin cancer involved visuals on white skin only, our natural bias is to that one perspective, and that bias can be the difference between life and death.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of ELLE Magazine.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io